Turning philanthropy sideways: from vertical to horizontal philanthropy

Observatorium 13 | 01.04.2017 | The concept of philanthropy is usually identified with the vertical flow of resources from those of high net wealth (the rich) to those of lesser means (the poor), as exemplified in the international aid system. In this familiar model, resources (typically financial) are provided by one community to assist or benefit another.

External resources are mobilised to address a deficit and fill a gap. While this is one key representation of giving and typically the first one that comes to mind when we hear the word “philanthropy” – meaning a “love of human kind”, it is not the only one. There is an alternative model based on the horizontal flow of resources from people within the same community. In this case, people held together by a shared identity, context and general situation mobilise the money, time and talent that exists within their community to assist or benefit one another. In this case existing resources are redistributed, getting them to where they are needed most. This practice, exemplified in selfhelp, reciprocity and mutual assistance, is typically found in cultures and contexts where the way of life is grounded in collectivism rather than individualism.

I shall argue that horizontal philanthropy is an alternative model to the more widely recognised vertical form and that is it indeed important. The first part of this paper describes horizontal philanthropy using an African perspective and the lived reality of the poor. This sets up part two, which is a consideration of why horizontal philanthropy matters, using the case of development practice. I shall consider the substance of horizontal philanthropy through a practical tool called the ‘horizontality gauge’2 ‒ an organisational behaviour measurement instrument developed for community foundations, an institutionalised form of community philanthropy found all over the world.

1: What is horizontal philanthropy?

Horizontal philanthropy3 , refers to people within a community, either as individuals or in a group, giving to one another to get the resources that they have to where they are needed most. This is done in order to address a problem or challenge in their own community that no one individual can tackle alone. In this instance, the “giver and receiver “are not separated, as they are from the same community and their exchange is not intermediated by an institution; rather it is direct ‒ person to person or group to group. Barry Knight highlights four distinguishing features of horizontality4.

It:

- requires people to give of their own assets and resources;

- can be individual to individual as well as collective action – whereby individuals pool resources to address the need of one, a few or many;

- locates givers and recipients as equal in the philanthropic act (i.e. the givers are not ‘richer’ than the recipients); and

- can be connected to the idea of “collective philanthropy” ‒exemplified in the tradition of giving circles whereby people pool what they have and then redirect their collective assets strategically to benefit their community.

Horizontal philanthropy is witnessed around the world, typically where there is a strong sense of collectivism in society. It has been written about in Canada with reference to the first nation’s people and in New Zealand focusing on the Māori. It is also a recognised feature of civil society in Pakistan and Mexico. I shall focus on the African setting and the context of poverty. This case allows me to draw on five key dimensions of horizontality5 that surfaced using grounded theory by my colleagues and me at the Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town, in South Africa. A Ford Foundation research grant allowed us to examine the situation of people living in poor communities in Namibia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and South Africa. Local research teams using a total of 11 vernacular languages asked community members four basic questions: (1) what is help; (2) who[m] do you help and who helps you; (3) what forms of help are used for what purpose; and (4) why do you help? We used the term “help” instead of philanthropy, because the latter is not widely used on the continent. Furthermore, people ‒ rich or poor ‒ do not necessarily see themselves as philanthropists. The term, however, is widely understood and easily translates into local languages.

What we call needs and networks is the first dimension to highlight, as it allows us to appreciate horizontal philanthropy as a system of giving based on a need and networks that provide help or assistance. The type of need to be satisfied (which could be urgent, immediate or unplanned such as a fire or other emergency, or a normal, small and anticipated need such as having to pay school fees) determines the suitable help network. In the case of normal needs, a personal set of connections is drawn upon – for example a neighbour or people you associate with in a club or group. For an urgent need, the network tends to expand and could typically involve receiving assistance from people not personally known to you – for example, in the case of a shack fire in a township people will donate cloth and blankets for the victims as well as contribute voluntary labour in helping to sort through the rubble.

The second dimension speaks to transactional content used to satisfy a need. A range of capital – be it money, goods in kind, labour power, and even emotional support (such as prayer) – is mobilised, most often a combination of these is contributed. This varied collection of capital allows a person, no matter how dire the circumstance, to help and, in doing so, to satisfy the reputational requirement of “giving, no matter how little’. Giving is critical for reinforcing social cohesion and allows a person to maintain their eligibility to be assisted by others and access help networks.

The third dimension relates to purpose. Help transactions can be judged as either useful to maintain the living status, conditions and prospects of the one in need ‒ preventing them from slipping into further hardship, or to increase the prospect of escaping adversity. Put another way, help is typically used with two ends in mind: it can prevent a situation from getting worse by maintaining the current conditions (for example, by making sure your neighbour’s children have something to eat) despite forces pushing in a worsening direction, or it can allow for movement away from adversity (for example, by assisting youth to get an education, be trained or find work).

The fourth dimension we call “norms and conventions”. It captures the idea that the way people reallocate resources within a community is not random or haphazard. Decisions determining who is and who is not eligible to be helped are made on the basis of unwritten yet widely used conventions, customs and sanctions, and are continually updated, transaction by transaction, for reinforcement or attrition of the network’s value to those who use it. To illustrate ‒ if a person is given money to help “make ends meet” as part of the transaction, the agreement for payback will be set. If circumstances transpire against this agreement being fulfilled, the system typically allows for adaptation and a renegotiation of the terms and conditions. However, when an agreement is not honoured, sanctions apply. This could be a scolding, a decrease in reputational capital or being denied help the next time around.

The final dimension is the philosophy of collective self. This hinges on a moral imperative to assist others, rather than being guided by an individualist consciousness. The term “Ubuntu”, widely used in South Africa and meaning “I am because you are.” points to helping others as a way of life. This way of seeing life and the interdependence between people, is simply a way of being. It is how thing are done. However, giving is not always an option ‒ rather it can be expected of a person or group often by virtue of their status (e.g. age, gender or wealth) or their relationship to others (relative, neighbour, school mate, or shared ethnic identity). Helping can be laced with responsibility and obligation and can even carry the weight of burden. In South Africa, the term “black man’s tax” has emerged in the last few years as the post-apartheid generation of young people seeks to be economically mobile, moving out of entrenched poverty. It can be that as people seek to advance, they feel “held back” by the need to “give back”.

The phenomenon I have just described by breaking it down into five key features is not insignificant. Rather, it is massive ‒ being known and practised on a daily basis across the African continent by a billion people. Furthermore, this norm inspires 40 billion dollars of diaspora giving that flow into the African continent annually as remittances. This scale makes horizontality too significant to disregard. However, until recently, it has sat below the radar of how philanthropy is conceptualised and understood. Highlighting it reveals that existing theories of philanthropy are incomplete or partial because they have not been interwoven with experiences outside of the EuroAmerican experience. This means that study and practice of philanthropy can strengthen theory by making it polycentric. Horizontal philanthropy makes a large contribution to this ‒ more needs to be known about its forms and expressions in diverse cultural settings and contexts, and how horizontality co-exists and blends6 with verticality. The growing recognition of philanthropy as a field of academic study and practice, marked in part by new centres for the study of philanthropy emerging around the world (most recently in 2016 in Scotland, India, and South Africa), is an encouraging development opening up more spaces for continued pursuit and learning about theory, practice and their interplay.

2: Why does horizontal philanthropy matter?

I shall now move from this foundational understanding of what horizontality is, to considering its contribution to development practice. I do this by describing a practical tool called the ‘horizontality gauge’. This instrument combines measurement, horizontal philanthropy, vertical philanthropy and the organisational behaviour of a community foundation. It is something I developed in the last five years with the help of six community grantmakers in South Africa.

The gauge allows community foundations to assess the extent to which they place community dynamics at the centre of their practice. It is a response to the finding of the Monitor Company Group7 that while the foundation model positions community as essential, it is seldom the case that community leadership, knowledge and favoured ways of working are leveraged and build from as a strategic advantage.

Thirty workshop participants from southern Africa8 reached a similar conclusion: “While organisations know about and are familiar with how communities help themselves, they seldom view it as ‘developmental’.” Participants went on to say that: “Grantmakers don’t start where communities are. We expect communities whether they are here or there, to come up to our level. But we don’t go to the level of communities”9.

The study findings maintain that the focus of community foundations is on building organisations rather than communities.

The primary concern is their own growth and sustainability. To shift this trend and address the “practice- aspiration” gap, community foundations need to take stock of how they work, determine what is out of line and correct it. This proposition proved problematic as, prior to the development of the horizontality gauge, there was no established way to do this. The field of community philanthropy did not have a set of signposts or measures to determine whether a foundation was taking the community dynamic into account. This is where an understanding of horizontality has been welcome and catalytic in enabling the development of a measure that was previously missing – namely a way to gauge the directionality, vertical or horizontal, of a community foundation’s behaviour. This advance is made possible by using the five dimensions of horizontality and juxtaposing them to verticality.

I shall unpack this, revealing how a comparison of the horizontal and vertical – that is how communities help themselves and how aid helps communities – can offer the sector five spectrum or ranges of behaviour against which foundation practice can be considered.

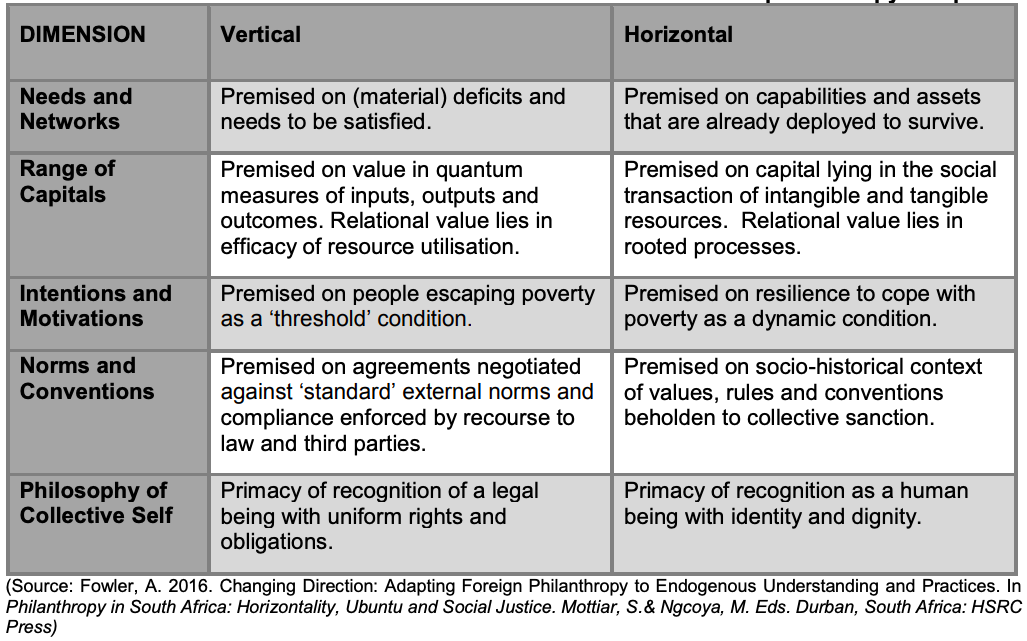

To start, Table 1 below compares the vertical and the horizontal against the five dimensions.

As you can see, the world is viewed differently by the aid industry and by communities. The vertical considers need to be a deficit or gap that is filled by adding more resources.

Table 1:Vertical and horizontal philanthropy compared

The tendency is to prioritise money and focus on how much ‒ viz. the quantum. Furthermore, verticality is concerned with helping people escape poverty and does so by entering into legal contracts and agreements detailing commitments related to inputs and outputs. Also from this perspective, people are approached as legal beings – citizens with rights. In contrast, communities are concerned with using and reallocating what they have to satisfy need and solve problems. They mobilise all types of capital available to them – not just money, and place value on the act of helping rather than the amount of help provided. Rather than being legally binding, community help is premised in social contracts, and grounded in accepted ways of doing things. Help can be given to maintain a situation (hold things level) or to advance – improving the situation. In horizontality, communities pay attention to identity and the dignity of people for a focus on their humanity.

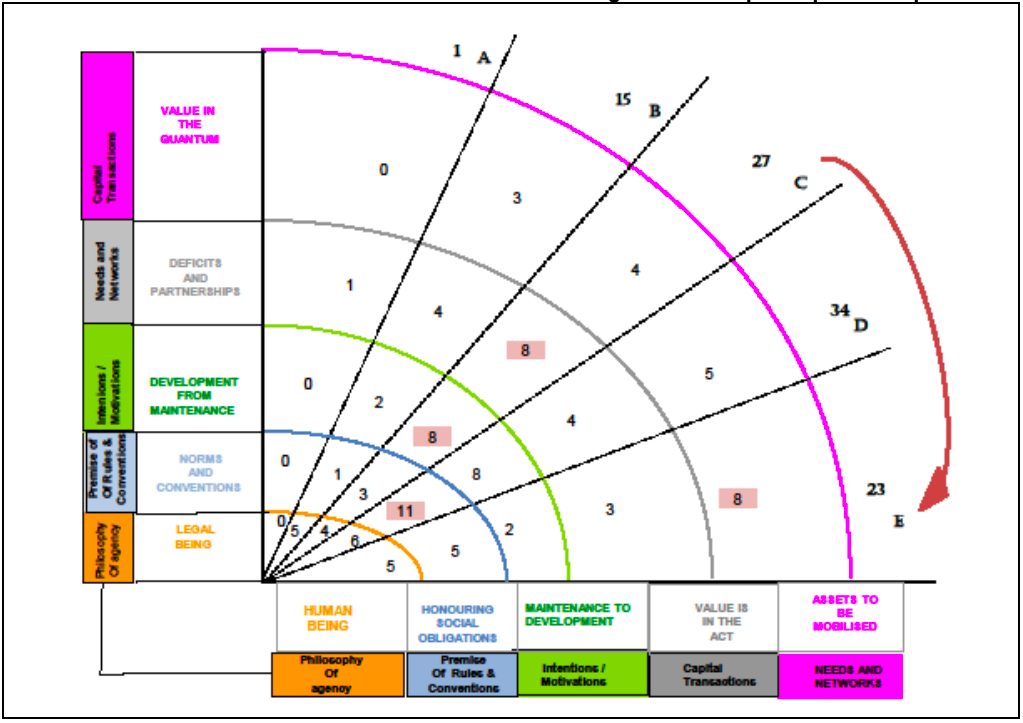

On distinguishing between horizontality and verticality as being different and representative of two extremes of ends of a spectrum (see Figure 2 for a visual illustration of this), I combined this with Porras and Hoffer’s10 four elements of an organisation, drawing out the fundamentals of how organisations are set up and offering a framework for asking questions and selfassessing.

The first element considered is organising arrangements. These are the formal structures and systems used to manage an organisation, for example administrative and payment systems and policy and procedures such as the management of costs and information. Next, are social factors. These are the social processes that make up an organisation’s culture and can include values, how decisions are made, and how members of staff relate to both one another internally and to external stakeholders. Third is technical know-how. These are the inputs that an organisation uses to achieve a desired result. These “tools of the trade” could, for example, include financial grants or capacity building interventions such as training materials or a mentorship programme to assist a community group. It could also include the skills and expertise of staff members.

The last element is physical setting. That is, the location of the organisation, as well as its look and feel for both staff and external stakeholders, taking into account factors such as its size, accessibility and environment.

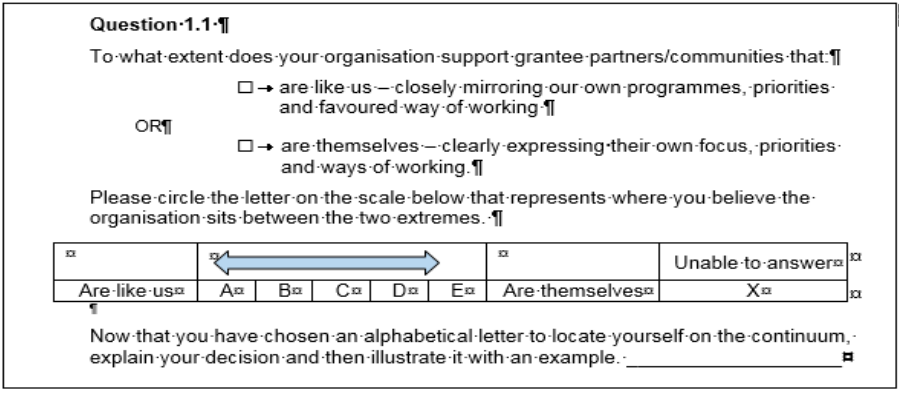

Using this as my framework – viz. the juxtaposition of verticality and horizontality using five dimensions and four elements of an organisation as points of interrogation, I then developed a 4×5 matrix and came up with 20 indicators of horizontality. These were turned into a series of questions for an individual questionnaire on organisational behaviour for completion by members of community foundations. For each question (as illustrated by the sample question in Figure 1), respondents scored organisational behaviour ‒ whether it was “more like this” (verticality) or “more like that” (horizontality) ‒ and then had to provide an example to substantiate the score.

Figure 1: Example of question structure and phrasing

The responses to all questions for all the respondents were combined and plotted visually on a philanthropic arc in Figure 2, revealing something about the horizontal or vertical direction of organisational behaviour.

You can see that the arc is structured on a vertical and horizontal axis providing a spectrum of behaviour ‒ at one end anchored in the aid industry’s favoured way of working and at the other end community bias, and made up of five arcs based on the five dimensions. The A to E quadrants on the arc mirror the scoring options on the five-point Likert scale used in the questionnaire and signalled in Table 1. The illustrative example used reveals that the organisation in question has a strong horizontal pull as shown by the score of 27 and 34 in quadrants C and D respectively and a weaker vertical pull as shown by a score of 15 and 1 in quadrants B and A respectively.

Figure 2: A completed philanthropic arc

The visualisation of the scores is unpacked with organisation members in a facilitated conversation or member check:

- What does this tell you? (we unpack each arc)

- Does it make sense to you?

- Is that the “us” you want to be? (i.e. is it who you say you are)

- What does this mean for behaviour and self-correction or reinforcement?

The process of completing and discussing the questionnaire takes a maximum of three hours and allows for a new kind of reflection and internal conversation. Specifically, it offers organisations an organisational development tool that can be used longitudinally, tracking changes in behaviour over time. It can also offer donors and membership networks of community foundations an instrument to add to their monitoring and evaluation toolkit, enabling them to measure behaviour and performance across organisations – joining the dots for a sector-wide appreciation of the directionality of behaviour.

The example of the horizontality gauge is only one way in which horizontal philanthropy in the African context has been applied to practice. Yet this example may deepen your understanding of the substance of horizontality and its importance to the practice of institutionalised community philanthropy. Additionally, it may peak your curiosity and interest in reflecting further on the contexts in which you work for a systematic understanding of the community dynamic and what it could mean for your own practice.

Conclusion

In engaging with horizontal philanthropy as an alternative to the more familiar vertical model philanthropy, we have to address a number of implications which arise and test our understanding.

Firstly, the language we use in philanthropy becomes problematic. Horizontal philanthropy offers an alternative way to understanding philanthropy – yet it is hard to grasp this coexisting possibility when operating within the confines of the “old’ mainstream or conventional philanthropy language. In short, the term ‘philanthropy’ does not work – givers rich and poor on the African continent, and possibly in other contexts, don’t identify with it. Accordingly, horizontality brings with it the need to change the terms and language used. So this takes us back to words like ‘help’, ‘giving’ and ‘gifting’.

Secondly, horizontality challenges us to reflect on the term ‘institutionalisation’ and what is meant by it. The term ‘institutionalised philanthropy’ is widely used as a reference to the formal and registered. Though horizontal philanthropy does not comply with these criteria, its expressions are widely recognised and exist in known forms ‒ perhaps this too is ‘institutionalisation’ and the framing of the concept would therefore have to be broadened.

Next is the issue of theory. Until we integrate experiences outside of Europe and America into philanthropic theory, the field will continue to operate with prejudiced and incomplete understandings and concepts. To make theory in philanthropy stronger, work in theory building needs to be polycentric ‒ having multiple centres of importance and consideration.

Finally, I shall end by stressing the issue of scale and magnitude. Practices of self-help and mutual assistance that characterise horizontal philanthropy are organic and practised not only in Africa but also in other parts of the world. It is a widespread rather than unique phenomenon. Its scale should not be underestimated, as disregarding it would be to turn our backs on a massive phenomenon.

[1] This paper was given as a presentation at a seminar entitled” “Philanthropy: today? Philanthropy: tomorrow”, held on 12‒13 October 2016 and convened by the Centre for the Study of Philanthropy and Public Good, University of St. Andrews, Scotland.

[2] Wilkinson-Maposa, S. 2016. Data needed… and more besides. Alliance 21(4): 52‒53.

[3] Wilkinson-Maposa, S., Fowler, A., OliverEvans, C. & Mulenga, C.F.N. 2005. The poor philanthropist: how and why the poor help each other. Cape Town, South Africa: The Southern Africa-United States Centre for Leadership and Public Values, Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town.

[4] Knight, B. 2012. The value of community philanthropy: results of a consultation. Washington, District of Columbia: Aga Khan Foundation, USA & Charles Stewart Mott Foundation.

[5] Wilkinson-Maposa, S. & Fowler, A. 2009. The poor philanthropist II: new approaches to sustainable development. Cape Town, South Africa: The Southern Africa-United States Centre for Leadership and Public Values, Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town.

[6] ibid.

[7] Bernholtz, L., Fulton, K. & Kasper, G. 2005. Executive summary. In On the Brink of New Promise: The Future of U.S. Community Foundations. San Francisco: Blue Print Research and Design, Inc. & the Monitor Company Group. framing of the concept would therefore have to be broadened. Next is the issue of theory. Until we integrate experiences outside of Europe and America into philanthropic theory, the field will continue to operate with prejudiced and incomplete understandings and concepts. To make theory in philanthropy stronger, work in theory building needs to be polycentric ‒ having multiple centres of importance and consideration. Finally, I shall end by stressing the issue of scale and magnitude. Practices of self-help and mutual assistance that characterise horizontal philanthropy are organic and practised not only in Africa but also in other parts of the world. It is a widespread rather than unique phenomenon. Its scale should not be underestimated, as disregarding it would be to turn our backs on a massive phenomenon.

[8] Hosted in 2006 by the Centre for Leadership and Public values, Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

[9] Workshop participant. Community Grantmaking and Social Investment Programme, Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town. July 2006.

[10] Porras, J.I., & Hoffer, S.J. 1986. Common behaviour changes in successful organisation development efforts. The Journal of Applied Behaviour Science. 22(4):477–494.